A Bloodworm is not for the faint of heart or the easily frightened. Be wary since, despite their fleshy appearance, these underwater tubes are not to be handled lightly.

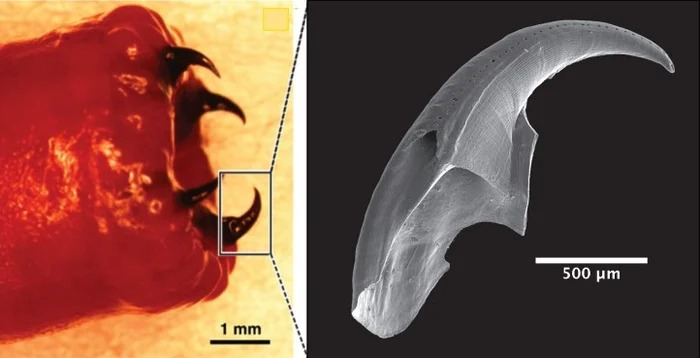

Bloodworms (also known as ‘bristle worms‘) dig deep into the muck along the seafloor before emerging to capture prey and competitors. Their fearsome jaws are partially made of copper and packed with paralysing venom.

Bloodworms are detested by everyone, especially those who make a living studying them.

“These are very disagreeable worms in that they are ill-tempered and easily provoked,” says Herbert Waite of the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Department of Biochemistry.

When they come into contact with another worm, they struggle with their copper jaws, according to the author.

Metal Bloodworm teeth, de-mystified.

A graduate student in the Waite Lab, William Wonderly, investigated how the bloodworm Glycera dibranchiata makes copper for its jaw. According to the findings of the study, copper makes up about ten percent of the entire structure of the jaw, with protein and melanin accounting for the rest.

The combination of copper and melanin found in bloodworm jaws has previously been proven to provide fangs high abrasion resistance, allowing them to stick around for over five years after formation.

The new research revealed a structural protein that facilitates the successful assembly of these chemical components by dissected bloodworms, jaw tissue, and studying in vitro cell culture.

The researchers believe that the effectiveness of the protein in question – termed multi-tasking protein (MTP) – could pave the way for the creation of novel material production techniques.

“We never expected protein with such a simple composition, that is, mostly glycine and histidine, to perform this many functions and unrelated activities,” says Waite.

“These materials could be road signs for how to make and engineer better consumer materials,” the author argues.

MTP, according to the researchers, performs a variety of chemical roles from start to finish in the jaw manufacturing process.

It serves as an organiser and fabricator by assembling the resulting mixture of protein, copper, and melanin that forms the jaws of the bloodworm’s proboscis. It also binds copper (which comes from maritime sediment) and catalyses the synthesis of melanin.

The researchers describe it as a difficult procedure that would require a lot of effort and specialised equipment to replicate in a laboratory setting with standard equipment.

It would be a significant step forward in materials science if we were able to replicate it — whether using natural MTP or simulating analogous chemical characteristics.

The article’s author stated, “The combination of chemical simplicity and functional versatility in MTP holds tremendous potential for bio-inspired and natural materials processing.”

When you think about it, all of this brilliance came from a bloodworm’s mouth, which is incredible. It’s possible that they’re not as bad as they appear.

Matter has released the research findings.

Story Source: Original story provided by Cell Press. Note: Content may be edited for style and length by Scible News.

Reference

William R. Wonderly, Tuan T.D. Nguyen, Katerina G. Malollari, Daniel DeMartini, Peyman Delparastan, Eric Valois, Phillip B. Messersmith, Matthew E. Helgeson, J. Herbert Waite. A multi-tasking polypeptide from bloodworm jaws: Catalyst, template, and copolymer in film formation. Matter, 2022; DOI: 10.1016/j.matt.2022.04.001