Nearly 42% of adult Americans in the US suffer from obesity, which raises their risk of diabetes, cancer, and other chronic disorders. A limited amount of research has examined the relationship between eating late and the three primary elements that influence body weight and, consequently, the risk of obesity: calorie intake, calorie expenditure, and altering the molecular structure of fat tissue.

Though late-night snacking is discouraged in standard healthy diet advice, little research has examined the overall effects of late eating on all three aspects that influence body weight.

In a recent study, researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, one of the healthcare network’s founding institutions, showed that meal timing significantly affects a person’s metabolism, sense of hunger, and metabolic pathways in adipose tissue. The research results were released in Cell Metabolism.

The Medical Chronobiology Program at the Brigham Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders is where Dr. Nina Vujovic carries out her research. The team looked into whether the time of day we eat matters if all other factors in the study remain constant.

Methodology.

The study by Vujovic, Scheer, and colleagues examined 16 patients with either overweight or obese BMIs. Two different laboratory tests were conducted on each subject, one using an early mealtime schedule and the other using the same meals four hours later.

In the final two to three weeks before starting each in-lab regimen, participants kept their regular sleep and waking hours, and in the final three days before entering the lab, they ate the same meals at the same times at home.

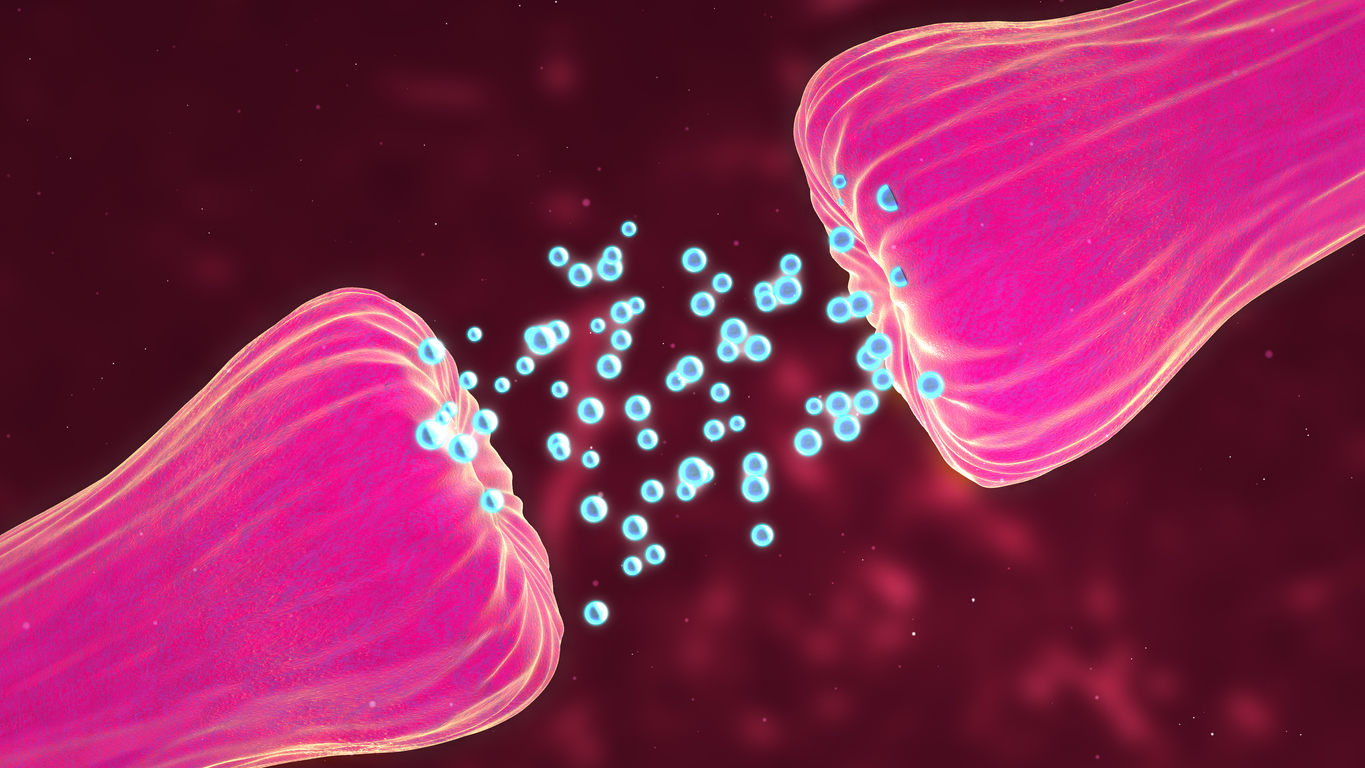

The researchers were able to measure the participants’ body temperatures and energy expenditure as well as regularly document their hunger and appetite in the lab thanks to the individuals’ frequent little blood samples. Adipose tissue samples were taken from a sample of people during laboratory testing to examine gene expression levels/patterns between early and late feeding methods. As a result, they were able to look at how dietary practices affected the molecular networks that underlie adipogenesis, or the process by which the body stores fat.

Findings and implications.

The hormones leptin and ghrelin, which regulates hunger and appetite, were discovered to be significantly impacted by eating later. Leptin levels were considerably lower in the late dinner condition compared to the early lunch condition throughout the course of a 24-hour period. In addition to changed gene expression in their adipose tissue, those who ate later had slower calorie expenditure, greater adipogenesis, and less lipolysis. These results imply that physiological and molecular reasons for the link between eating later in the day and an elevated risk of obesity are converging.

These findings, in Vujovic’s opinion, not only confirm the results of a substantial body of research that suggests that eating later may raise the risk of obesity, but they also provide new insight into the mechanism by which this may be the case. Researchers were able to identify changes in the numerous regulatory systems involved in energy balance, a sign of how our bodies use the food we eat, using a randomized crossover trial. This methodology allowed them to control for behavioral and environmental factors like physical activity, posture, and sleep.

To make sure that their findings are applicable to a larger population, Scheer’s team intends to involve more women in the next tests. Menstrual phases were taken into account when the study was being planned, which decreased confounding but made recruiting women more challenging because there were so few female participants (five).